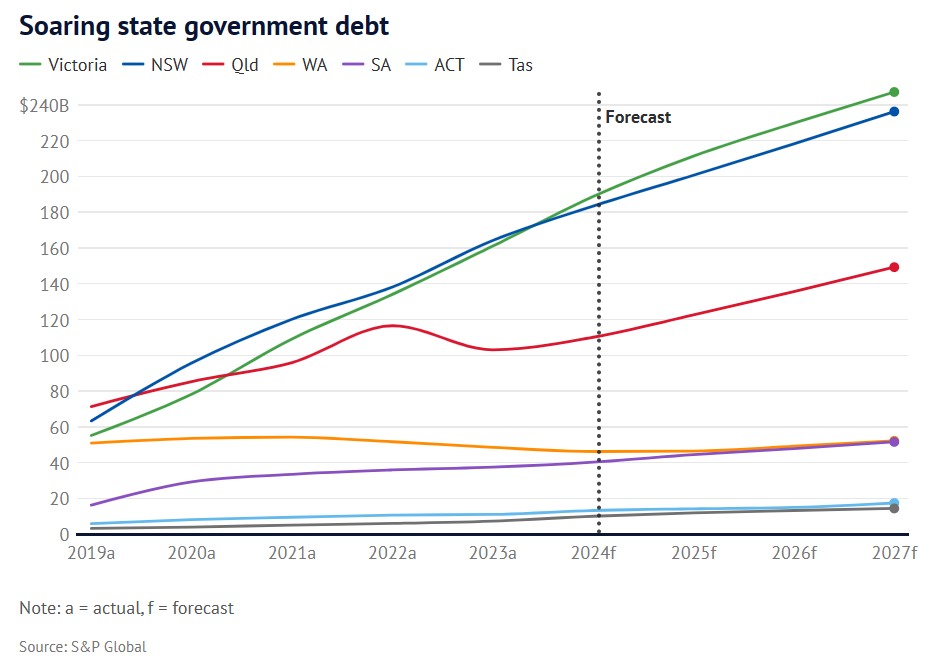

There is growing political discussion in New Zealand around the idea of introducing rate capping, an approach already implemented in parts of Australia, particularly New South Wales and Victoria. At first glance, rate capping can seem like a well-intentioned measure. Limiting how much councils can increase rates each year appears to offer some protection for households feeling the pressure of rising living costs. However, beneath this surface appeal lies a policy that is deeply unsuited to New Zealand’s governance structure, legal framework, and community values. More importantly, the negative consequences of rate capping, clearly visible across the Tasman, paint a cautionary tale of eroded infrastructure, declining services, and weakened communities and democracy.

New Zealand’s system of government is structurally different from Australia’s in one critical way: the New Zealand government operates under a two-tier system, with central and local government. In contrast, Australia employs a three-tier system comprising federal, state, and local levels. This distinction has significant implications. In New Zealand, local government carries a much greater share of responsibility for infrastructure and services than its Australian counterparts. Councils are responsible for managing drinking water, wastewater, stormwater, local roads, libraries, parks, waste services, economic development, and in many cases, civil defence and resilience planning. In rural areas in particular, councils are often the only visible and engaged layer of government delivering real services to real communities.

In Australia, much of this responsibility is carried by state governments. When local councils face financial constraints, states can and often do step in with additional funding, grant schemes, or direct service delivery. In New Zealand, that simply doesn’t happen. Local governments are expected to stand on their own feet and fund the services and infrastructure their communities need. Yet, despite this far broader role, central government funding for New Zealand councils is modest. Compared to Australian councils, New Zealand local authorities receive a much smaller proportion of their revenue from central government. Unless the New Zealand government is prepared to increase the amount it invests in councils significantly, the imposition of a rate cap is not just unwise—it is reckless. It would shift risk downward without compensation, placing enormous strain on already constrained local authorities.

Layered on top of this is the legislative and governance framework that governs New Zealand councils’ operations. The Local Government Act 2002 and the Local Government (Rating) Act 2002 both enshrine a strong commitment to local autonomy, financial prudence, and community consultation. Councils are legally obliged to operate a balanced budget under Section 100, to consider all reasonably practicable funding options under Section 101(3), and to adopt transparent and predictable funding and revenue policies under Sections 102 and 103. These requirements are not theoretical; they are actively enforced, and councils are audited against them. In addition, councils must develop Long-Term Plans every three years and Annual Plans each year, both of which can require robust community engagement. These plans are the primary means by which local people influence local services and investment.

The introduction of a rate cap cuts directly across these responsibilities. It overrides the council’s obligation to assess local funding needs and denies the community’s voice in deciding what level of service they are willing to fund. It reduces a complex, locally tailored process of consultation and decision-making into a rigid central dictate. Councils can still ask their communities what services they want, but if the funding limit has already been imposed from above, those conversations become meaningless. They become hollow gestures, with councils forced to say, “we asked, we listened, but we’re not allowed to act.”

Another fundamental flaw in rate capping is the notion that a single, fixed annual percentage increase is suitable for all councils. This assumption is not only flawed but also deeply unjust. Local government is not homogeneous. Every council in New Zealand has its own set of circumstances: different population growth rates, asset profiles, infrastructure lifecycles, and geographic challenges. A rapidly growing urban council might be able to offset rising costs with new rateable properties and development contributions. A rural council with no growth, a declining rating base, and a long list of ageing assets will face an entirely different set of financial pressures. Yet rate capping treats them the same. This results in gross inequity, punishing councils that already operate with limited flexibility and little room for error.

Equally problematic is the mechanism often used to determine the cap, typically the Consumer Price Index. CPI tracks the average change in prices paid by households for a basket of goods and services. It is designed to reflect the cost of living for families, not the operational cost structure of a council. Councils do not purchase groceries and petrol. Their costs are driven by materials, labour, professional services, energy, construction, and increasingly, digital infrastructure and cybersecurity. For example, the prices of bitumen, concrete, and steel (essential inputs for roading and civil works) have increased significantly more than the CPI over the past five years. Similarly, wages in the public sector, including collective agreement obligations, have risen faster than CPI in many instances.

One area where the disconnect between CPI and council costs is especially stark is in technology and digital operations. Councils across New Zealand are undergoing digital transformation, transitioning from legacy systems to cloud-hosted, subscription-based ERP platforms that manage a range of functions, including payroll and budgeting, regulatory workflows, and community engagement. These systems are critical to service delivery and compliance. Yet costs in this area have been rising sharply. Many councils report year-on-year increases in their ERP and cloud services of 10–15%, particularly as vendors shift to usage-based pricing and compliance requirements become more stringent. These costs are not discretionary; they are essential. But CPI-based caps do not accommodate them.

We’ve already seen what happens when rate capping is applied in practice. In New South Wales, where rate capping has been in place since the 1970s, councils have repeatedly warned of declining service levels and deteriorating infrastructure. During the COVID-19 period, the disconnect became even more apparent. In 2023–24, while Sydney CPI was 5.3%, the rate peg determined by IPART was set at 3.7%. This figure was based on a lagged cost index that failed to keep pace with rising inflation, leaving councils stuck between rising costs and revenue ceilings they could not exceed. When councils do reach a breaking point, they are forced to apply for Special Rate Variations, requests to increase rates by 10% or more per year for several years. These variations often come with high administrative burdens and uncertain outcomes. They also represent a clear violation of intergenerational equity, as they delay investment until the next generation is forced to pay the price.

Intergenerational equity is one of the most important principles in local government funding. The idea is simple: each generation should pay for the services and infrastructure it consumes. Rate capping, by limiting councils’ ability to maintain and renew their assets, directly undermines this principle. Councils are forced to defer necessary works, patching potholes rather than resealing roads, making temporary fixes to stormwater drains, and stretching water infrastructure beyond its intended lifespan. Eventually, these decisions compound. The problem becomes bigger, more expensive, and more complicated to solve. And when the bill finally comes due, it’s not the people who benefited from the underinvestment who pay; it’s the next generation of ratepayers.

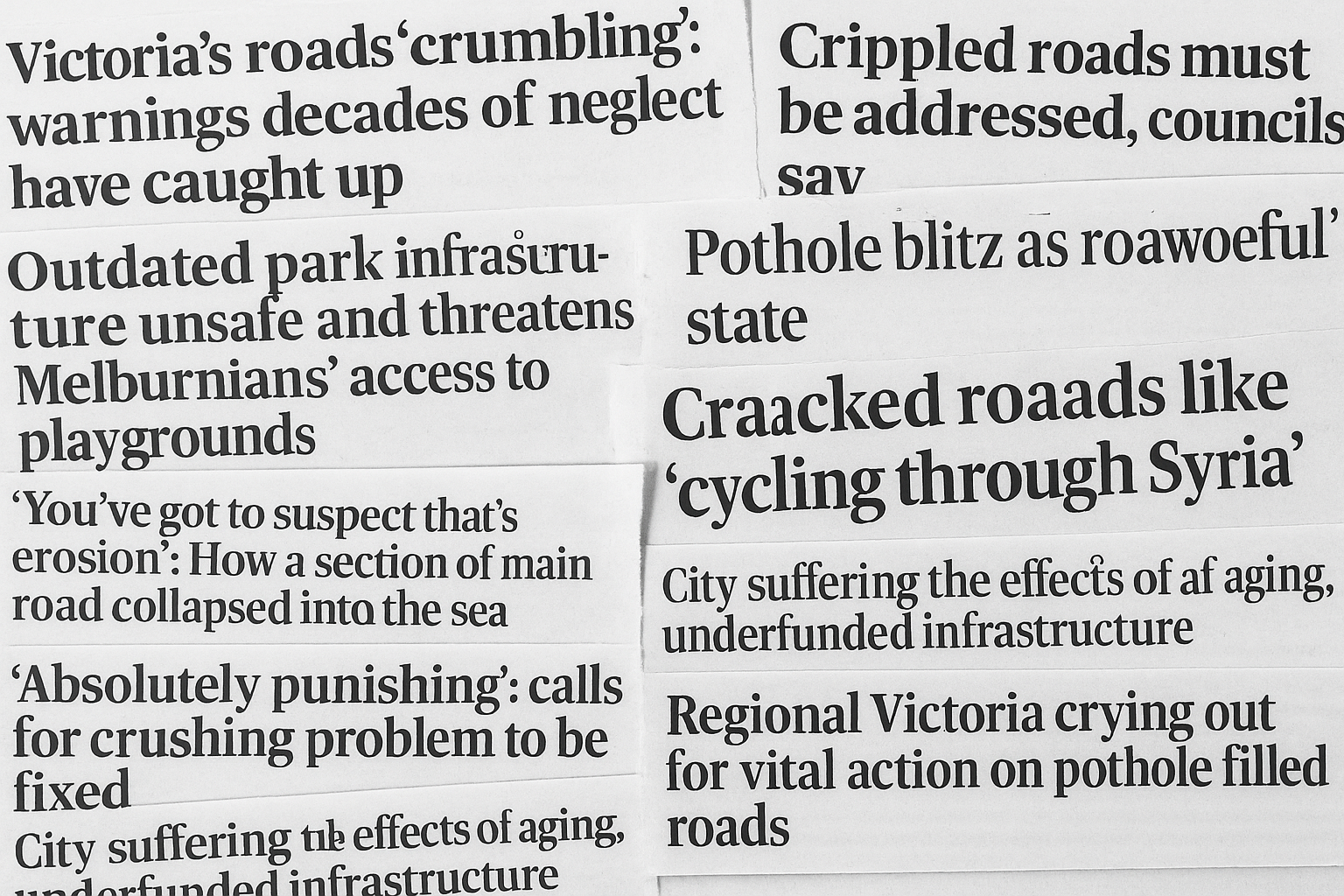

Victoria provides an even more dramatic case study. Since the introduction of rate capping in 2016, the consequences have become increasingly visible. In the 2023–24 year alone, regional road resurfacing dropped by 95%, from over 9 million square metres to just 422,000 square metres. Road maintenance funding fell from $201.4 million to $37.6 million. Councils deferred projects, cancelled capital works, and began issuing warnings about the long-term sustainability of their operations. Residents complained about potholes, closed parks, deteriorating footpaths, and declining service standards. Social media has been flooded with photos of unsafe roads and “band-aid” repairs, illustrating the slow erosion of public infrastructure. Meanwhile, staff within councils have faced increasing pressure. Many report burnout, difficulties recruiting, and diminished morale as their ability to do their jobs is steadily constrained.

This is perhaps the most insidious outcome of rate capping: it forces councils to move from being proactive planners to reactive responders. Instead of addressing problems early and cost-effectively, they are forced to apply “band-aid” solutions and let problems escalate until they become politically or legally unavoidable. By the time action is taken, the cost to fix the issue has multiplied—and the community has already felt the impact.

In the New Zealand context, this is not a risk we should take lightly. Our councils play a much greater role in community wellbeing than in many other countries. They are trusted institutions that deliver tangible services and help shape local identity. In rural areas, they are often the only real interface between residents and the machinery of government. New Zealand has an absolute appreciation for community values and local voice, and our system is designed to reflect that. Capping rates cuts directly against this ethos. It tells councils, and by extension communities, that their needs and preferences are secondary to arbitrary, centrally imposed rules.

Unless the government plans to dramatically increase its direct funding to councils—funding not just for roads and pipes, but also for systems, staffing, and compliance—then rate capping will be nothing short of an erosion of support. It will hollow out the ability of councils to deliver, maintain, and plan for the services people rely on every day. And it will do so silently, incrementally, in a way that becomes visible only once the damage has already been done.

New Zealand’s councils already operate under robust planning and accountability frameworks. Rather than capping rates, we should be helping councils to model future scenarios, engage meaningfully with their communities, and navigate financial pressure with flexibility and transparency. Councils should be supported—not constrained—the institutions that carry the weight of local democracy and public service delivery.

Rate capping may seem like a straightforward solution to a complex issue. But the evidence from Australia is overwhelming: it leads to underinvestment, inequity, democratic decay, and ultimately, failure. It is not compatible with New Zealand values, the structure, or the ambitions for the communities served.

New Zealand Councils are also responsible for the provision of community facilities that cannot exist commercially. Public swimming pools, libraries, community centres, theatres, museums, parks and sports grounds become inaccessible to most of the public under a commercial model. To be accessible and viable, they require rate funding. There is a real risk that, under rate capping, many of these community facilities will simply disappear from councils’ portfolios. Once gone, the investment to bring them back will be massive.

“Victorian councils count the cost of a decade of rate caps”

Councils are struggling to deliver expected services after a decade of capped rates. Regional authorities particularly lack alternative income, and central support remains limited.

“Number of potholes on Victorian roads almost triples in one year”

Reports from right here in Snap Send Solve revealed 8,912 potholes in 2022–23—nearly triple the previous year—forcing councils to pause long-term resurfacing in favour of temporary fixes.

“Potholes Ahead: Victoria’s roads face a dismal future”

Industry figures warn the resurfacing sector in regional Victoria has collapsed. Without regular renewals, roads crack and deteriorate rapidly—leading to expensive, long-term fixes.

Campaign: “Potholes for All Seasons”

The Coalition launched a photo campaign for a “Potholes for All Seasons” calendar, highlighting escalating dissatisfaction and a lack of substantive repairs. 91% of regional roads were ranked in poor or very poor condition.

“Sydney councils with most roads to fix revealed”

The NRMA’s report shows NSW council road repair backlogs rose from $2.8 b to $3.4 b in a year. Regional councils account for the majority. Despite this, federal funding is just $292 m against an average need of $574 m annually.

Parliamentary inquiry: “Rates not keeping pace with costs”

The NSW Legislative Council inquiry found the rate peg hasn’t kept pace with council cost growth. Recommendations include greater rate-setting flexibility and reconsidering how rates are structured.

“Rate peg a ‘body blow’ to struggling councils”

Council peak body LGNSW described the 2023–24 rate cap of 3.7% as a body blow—given inflation sat around 6%—leading to delayed infrastructure upgrades and staffing reductions.

“Shocking: North Sydney Council to vote on 111% rate hike”

North Sydney faced nearly a 90% rate rise due to a mismanaged pool redevelopment project, illustrating the risks of deferring infrastructure investment under capped funding.

“Ku-ring-gai Council proposes up to 26% rate rise”

Ku-ring-gai Council is considering a major rate hike—up to 26%—to fund ageing infrastructure and repay loans, underscoring how under-capping can create sudden rate shocks.

“Shocking suburban street isn’t fit to walk a dog on”

In Kempsey, NSW, residents described Albert Street as so damaged that even walking a dog feels unsafe. Despite millions allocated for roadworks, full repairs may take years due to budget limits.

“Victorian parliamentarians call for audit of public libraries”

Inquiry members raised concerns that library services are under strain, with funding formulas skewing regional allocations and state grants lagging behind cost growth.

“Library services flagged as at risk under capping constraints”

The Victorian Auditor-General noted rate caps challenge councils’ ability to maintain sustainable library services—key community hubs often at risk of cuts.

“Rural councils warn of closures to pools, playgrounds, libraries due to financial squeeze”

In a submission to federal inquiry, Rural Councils Victoria flagged that constraints on rate increases threaten core community assets.

“Northern Beaches Council proposes axe on events and vacation care amid bid for 40% rate hike”

Services like community events and childcare are facing cuts to address budget strain driven by rate capping and rising essential obligations.